Check Valve

Check valves are probably the most misunderstood valves ever invented. If you mention check valves to most plant personnel, the typical response is “they don’t work.” In fact, those personnel may well have taken out the internals or re-piped the system to avoid check valves. In other words, these valves are the least popular valve in use today.

This article will explore the basics of check valves, how they work, what types there are, how to select and install them, how to solve their problems, and, finally, why they are not always the cause of the problem.

Simply put, a check valve allows flow in one direction and automatically prevents back flow (reverse flow) when fluid in the line reverses direction. They are one of the few self-automated valves that do not require assistance to open and close. Unlike other valves, they continue to work even if the plant facility loses air, electricity, or the human being that might manually cycle them.

Check valves are found everywhere, including the home. If you have a sump pump in the basement, a check valve is probably in the discharge line of the pump. Outside the home, they are found in virtually every industry where a pump is located.

ارتباط با ما

Like other valves, check valves are used with a variety of media: liquids, air, other gases, steam, condensate, and in some cases, liquids with fines or slurries. Applications include pump and compressor discharge, header lines, vacuum breakers, steam lines, condensate lines, chemical feed pumps, cooling towers, loading racks, nitrogen purge lines, boilers, HVAC systems, utilities, pressure pumps, sump pumps, wash-down stations, and injection lines.

How They Operate

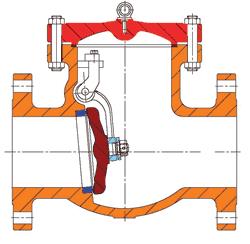

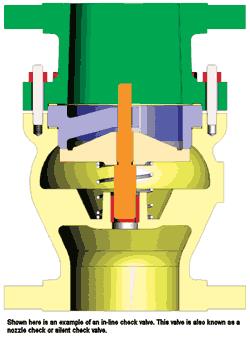

Check valves are flow sensitive and rely on the line fluid to open and close. The internal disc allows flow to pass forward, which opens the valve. The disc begins closing the valve as forward flow decreases or is reversed, depending on the design. Construction is normally simple with only a few components such as the body, seat, disc, and cover. Depending on design, there may be other items such as a stem, hinge pin, disc arm, spring, ball, elastomers, and bearings.

Internal sealing of the check valve disc and seat relies on fluid back-pressure as opposed to the mechanical force used for on/off valves. Because of this, allowable seat leakage rates are greater for check valves than for on/off valves. Metal sealing surfaces generally will allow some leakage while elastomers, such as Buna-N and Viton, provide bubble-tight shutoff (zero leakage). Because of this, elastomers should be considered for air/gas media, where chemically compatible, and low-pressure sealing.

So what is the ideal check valve?

Regardless of type or style of valve, the longest trouble-free service will come from valves sized for the application, not the line size, whereby the disc is stable against the internal stop in the open position or fully closed. When these conditions are met, no fluttering of the disc will occur. Unfortunately, most check valves are selected in the same way on/off valves are selected: based on line size and the desire for the largest Cv available. This ignores the fact that, unlike on/off valves, the flow conditions determine the internal performance of the check valve since its disc is always in the flow stream.

As mentioned earlier, unlike on/off valves, check valve internals are flow sensitive. If there is not enough flow, disc movement occurs inside the valve since the disc is always in the flow path. This results in wear, potential for failure, and a higher pressure drop than calculated.

Whenever a metal part rubs against another metal part, wear is a result, which leads to eventual failure of the component. A component failure can result in the valve not performing its function, which in the case of a check valve is to prevent reverse flow. In extreme cases, failure could result in the component or components escaping into the line, causing failure or nonperformance of other valves or equipment in the line.

Typically, pressure drop is calculated based on the check valve being 100% open, as with on/off valves. However, if the flow is not sufficient to achieve full opening and the check valve is only partially open, the pressure drop will be greater than calculated since the flow passage is restricted by the disc being in the flow path. In this situation, a large-rated Cv actually becomes detrimental to the check valve (unlike with on/off valves), resulting in fluttering of the disc and eventual failure. Such is not the case with some other valves. With a gate valve, for example, if the valve is fully open, the wedge is out of the flow path and the flow through the valve does not affect the performance of the wedge whether that flow is low, medium, or high.

Types

There are many types of check valves in use today. Some of the more popular types include: ball; dual plate or double-door; spring assisted in-line or nozzle or silent; piston or lift; and swing checks. As with other types of valves, specialty check valves can be found for special applications. While no one type of valve is good for all applications, each has its advantages. Take time to contact the manufacturer to assist in selection of the best check valve, especially if you are incurring problems with whatever type of check valve that is currently installed.

Selection

Among the many factors to consider when selecting a check valve are material compatibility with the medium; valve rating (ANSI); line size; application data (flow, design/operating conditions); installation (horizontal, vertical flow up or down); end connection; envelope dimensions, especially if replacing an existing valve to avoid pipe modifications; leakage requirements; and special requirements such as oxygen cleaning, NSF, NACE, CE Mark, etc.

Problem Solving

When replacing a check valve it helps to ask the following simple questions:

- “Why am I replacing this valve?”

- “What is the problem?”

Sometimes we get so busy or absorbed in other things, we forget that the cause can help with the solution. Common check valve problems include noise (water hammer), vibration, reverse flow, sticking, leakage, missing internals, component wear, or damage. However, it is worth mentioning that normally the real cause is the wrong style check valve for the application. In such cases, the problem is the application, not the check valve.

Two of the most common problems with check valves are reverse flow and water hammer. In both situations, a fast-closing valve is desired. Reverse flow can be costly, especially if it occurs at the discharge of a pump and the pump spins backwards. The cost to repair or replace the pump, plus the plant downtime, far exceeds the cost of installing the right check valve in the first place. With water hammer, you need a faster-closing check valve to prevent pressure surges and the resulting shock waves that occur when the disc slams into the seat, sending noise, vibration, and hammering sounds that can rupture pipelines and damage equipment and pipe supports.

If the internals are missing or exhibiting wear, two factors may be occurring. First, if the check valve selected does not have enough flow passing through to keep it against its stop, a valve with a lower Cv is needed to prevent the moving/fluttering of the internals. Second, if the check valve is used at the discharge of a reciprocating air or gas compressor, a valve with a damped design or dashpot to handle high-frequency cycling is needed.

Sticking can occur when scale or dirt is trapped between the disc and body bore. Leakage can happen from damage to the seat or disc or simple trash in the line. An elastomer is needed to provide zero leakage.

Installation

This sounds simple, but when installing check valves, point the “flow arrow” in the direction of the flow to allow the valve to perform its function. The flow arrow can be found on the body or tag. Make sure the valve type will work in the installed position. For example, not all check valves will work in a vertical line with flow down, nor will conventional or 90-degree piston check valves perform in a vertical line without a spring to push the disc back into the flow path. The disc in some check valves extends into the pipeline when the valves are fully open. This could interfere with the performance of another valve bolted directly to the check valve. If possible, install the check valve a minimum of five pipe diameters downstream of any fitting that could cause turbulence. Notice the phrase “if possible.” After all, how many check valves have you seen bolted to the discharge of a pump? Many! A good source of reference for installing check and other styles of valves is MSS SP-92 “Valve Users Guide,” published by the Manufacturers Standardization Society.

How Are Check Valves Like Doors?

Lastly, check valves can be compared to doors, like the door to your office or home. Typically, you open your office door at the start of the day and close it at the end, which is similar to what happens when a pump is cycled on and off. However, if someone stands at your door and constantly cycles it open and closed, what could happen? In most cases, the hinge pins would fail, since they are the weak link in the operation of your door.

Check valves face a similar situation. Pins, stems, springs, or other components that are constantly cycled can fail. That is why it is important to properly select check valves for their possible applications. A check valve with a high Cv in a low flow application is doomed from the start. In a short period of time it will fail, no matter what extraneous engineering feats were used to “make it tougher.” Unfortunately, the installed check valve is blamed for the failure, when in reality the culprit was the application. It is always best to review the application and service conditions with the manufacturer before purchasing a check valve to make sure the correct style is selected and avoid replacing a problem with another problem.